"Direct indexing makes tax return prep harder"

This appears to be an imaginary problem. But that's not the point.

⚾ Quick note: No mid-week email this week. I’ll be in Phoenix for spring training with my family.

"Direct indexing makes tax return prep harder"

Ask a room full of financial planners, advisers, and wealth managers about direct indexing, and it will split into camps.

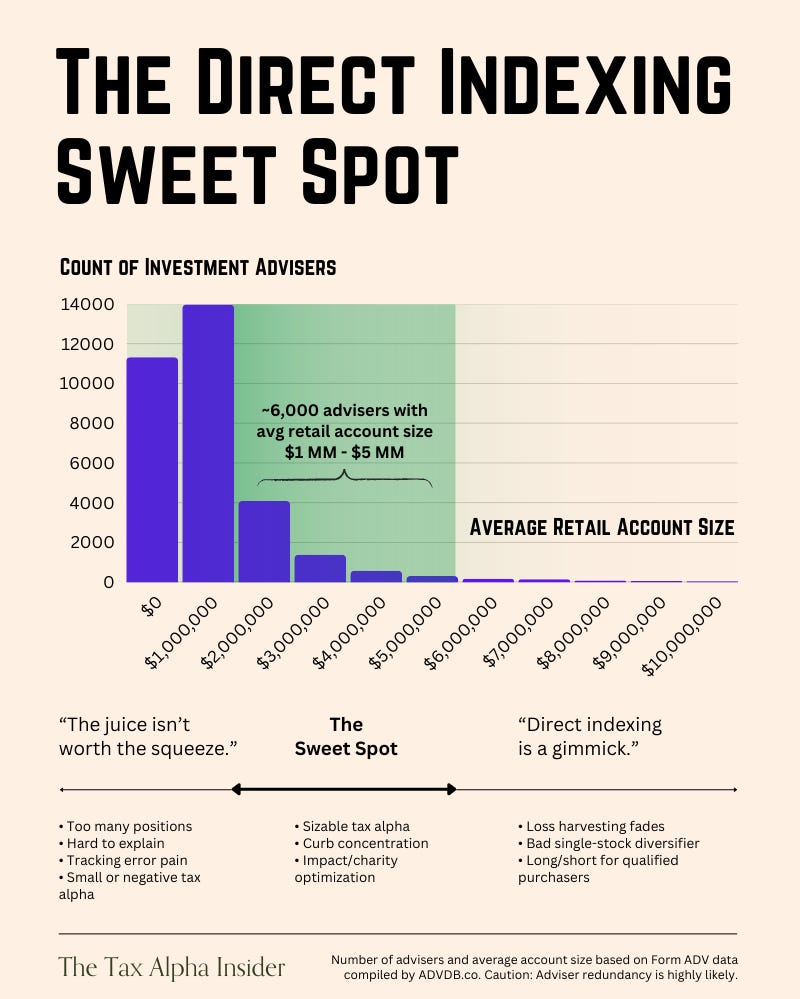

One camp thinks the direct indexing “juice isn’t worth the squeeze.”

The opposite camp thinks anyone disregarding direct indexing violates their fiduciary duty.

A third camp believes direct indexing is a gimmick.

I captured these camps in a graphic a while ago, summarizing what advisers had told me over the previous few months.

My pal Jerry Michael at Smartleaf wrote a thoughtful response cum rebuttal saying Direct Indexes Make Sense for Investors Worth Less Than $1mm and Over $5m.

But since I regularly hear complaints about how “inconvenient” direct indexing is, I recently polled my audience about whether direct indexing is annoying around tax time.

92% of respondents (68/74) said computers, not humans, solve the problem, which suggests it is likely imaginary (at least to my tech- and tax-savvy audience).

Maybe I was asking about the wrong inconvenience?

Jerry responded that advisers sometimes argue that “[direct indexing is] harder to explain” or that they don’t like “long statements,” which squared with what I've heard.

There are two things at play here:

Some technology is direct indexing “lite,” meaning it’ll check the direct indexing box but is a pain to use.

There are holdouts who think the juice isn’t worth the squeeze.

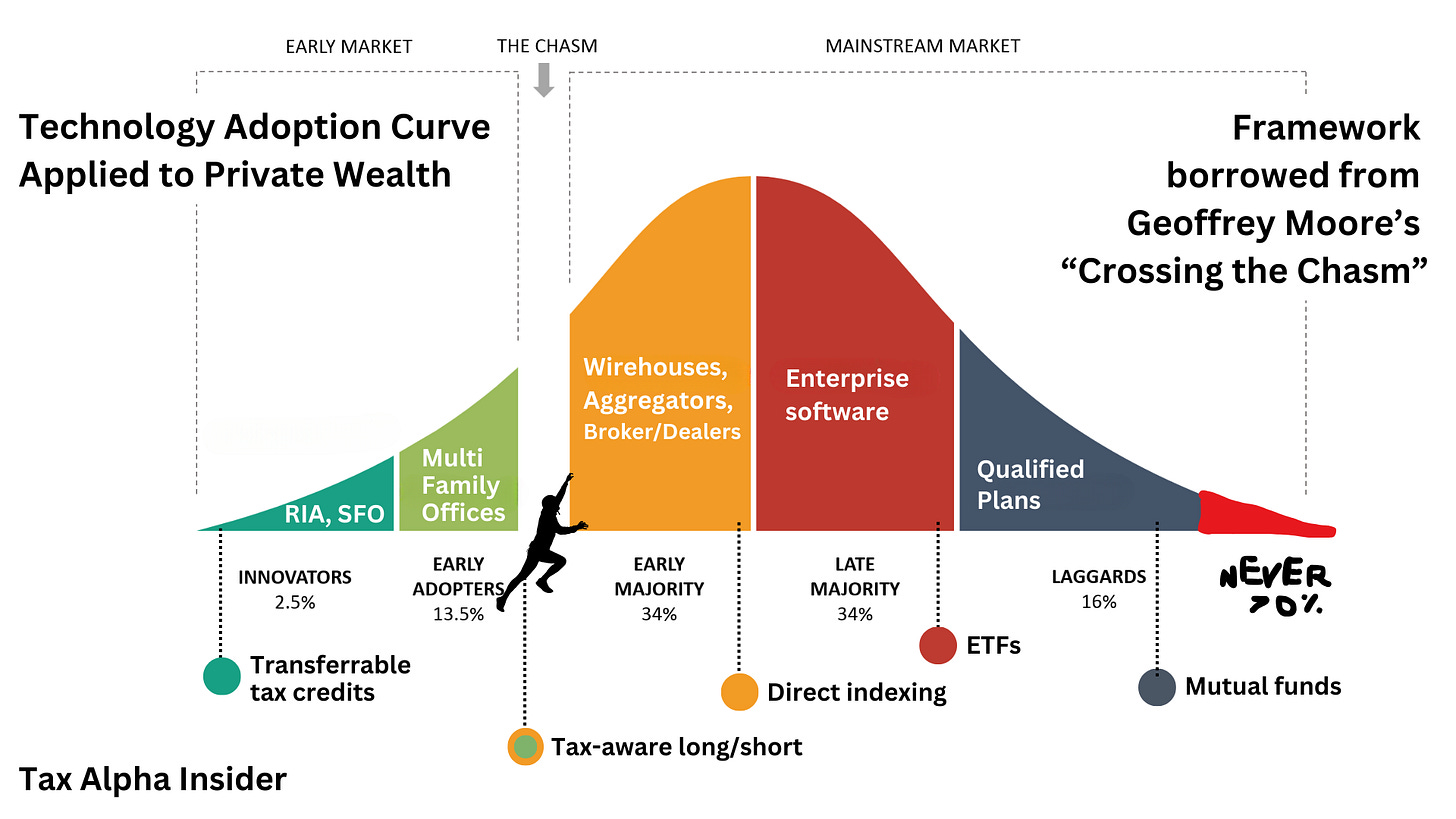

The technology adoption curve

Geoffrey Moore’s technology adoption curve from his excellent Crossing the Chasm comes to mind when I think of direct indexing adoption.